From the Archives: History of Wildlife Art

/ Society of Wildlife Artists

From the Archives

The following is an article from 2009, written by the late Robert Gillmor MBE (1936-2022), re-published on the occasion of the 61st annual exhibition by the Society of Wildlife Artists: The Natural Eye 2024.

After helping to found the Society of Wildlife Artists in the early 1960s, Robert served as its Secretary and Chairman for many years. He was elected President in 1984 and served for ten years.

History of Wildlife Art

© Robert Gillmor 2009

Origins

Animals were the principal subject for the earliest artists who portrayed those animals that were vital to their very existence. The paintings were hidden deeply on the walls of caves and only illuminated by the flickering light of fires and oil lamps. We do not know the true reason for these images, other than they must have been very important to their creators and probably had some form of magico-religious meaning. We do see, however, that the drawings were full of understanding of the living animal, brilliantly simplified and direct. They were clearly done by people who knew their subjects intimately, as they needed to, for such animals provided food, clothing, oils and much more. The very survival of early man depended on the skills of the hunter. Here, surely, are the clues to the importance and reasons for this art, so painstakingly daubed on the rough walls and ceilings of the caves where the artists and their families eked out their precarious lives.

From Symbolism to Science

Animals continued to have a place in art during the Middle Ages, but were treated as symbols, often appearing in religious works, particularly the marginal illuminations to hand written manuscripts. The mosaics and wall paintings found in Pompeii and other Roman settlements had featured many creatures, but it was not until the fifteenth century that animals began to be considered in their own right as serious subjects for artists. Discoveries in distant lands were brought back to Europe in the form of skins and drawings, and the scientists, who were beginning to study the natural world and its animals, needed illustrators to depict their finds. Renaissance draughtsmen, deeply interested in the world around them, such as Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), all made fine studies of animals. A century later artists such as Melchior d’Hondecoeter (1636-95) filled huge canvases with exotic birds in exotic landscapes, as well as domesticated fowl or birds to be seen in private collections.

It was from the more scientific approach to the study of animals in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that wildlife art as we know it has developed. The early writers on natural history wanted to illustrate the species they were describing and classifying. At first, woodcuts were the only way to produce images suitable for quantity printing. Books such as Francis Willughby’s Ornithologia, published in 1676, containing woodcuts by W. Faithorne, were inspirational for later followers.

Iconic Artists

The development of hand-coloured copper plate engraving gave illustrators more scope and made books on natural history very popular in the eighteenth century. The rather crude woodcuts were largely superceded by wood engravings. By engraving on the tight end grain of hard wood, such as Box, the engraver could produce much finer and more detailed work. It was Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) who developed the technique and produced sets of engravings of birds and mammals which were hugely influential and remain as popular today as they were when he was working in his Northumberland workshop.

Bewick was visited by the other great iconic figure of wildlife art, John James Audubon (1785-1851), who had come to Britain from America. He brought a portfolio of life size paintings of American birds, intending to find a printer and publisher. These remarkable paintings also had a huge impact and influence on artists such as John Gould (1804-1881). Audubon’s birds were masterpieces of draughtsmanship, dramatic and colourful. He was fortunate in his choice of printer, Robert Havell, who, together with his son, translated the paintings into superb hand-coloured engravings. The huge, elephant folio books that resulted, are today almost priceless.

John Gould brought bird illustration to a fine bibliographical art using lithography, which enables the artist to draw directly onto the stone, giving a softer, more flexible line. The black and white prints would then be hand-coloured by teams of skilled colourists. He also assembled a team of fine artists, including Edward Lear (1812-1888) and Joseph Wolf (1820-1899). Gould’s studies were largely based on bird skins, collected throughout the world.

As the nineteenth century drew to an end, many changes came about, particularly in methods of production, new printing processes and the development of photography. Archibald Thorburn (1860-1935) saw these changes and worked with them. He was one of the first wildlife artists to get into the field with a sketchbook and to work direct from life. He also broke new ground by creating paintings which no longer treated birds as scientific feather maps, but as pictures for their own sake. In this, he particularly appealed to the sportsman who wished to have pictures recalling their shooting forays in fine country landscapes.

The development of photography - and wildlife photographers were early exponents - freed artists from their traditional, illustration-based approach. In Sweden, Bruno Liljefors (1860-1939) showed the way, painting landscapes in which animals appeared as naturally as trees or rocks or a human figure.

A number of artists born around the turn of the century turned to painting wildlife subjects, largely based on their personal experiences in the field. For example, Peter Scott (1909-1989) painted the wildfowl, as a keen shot, he was trying to outwit on the marshes and estuaries of East Anglia. Of course, this activity soon ended and his early enthusiasm for shooting turned to a dedicated concern for conservation.

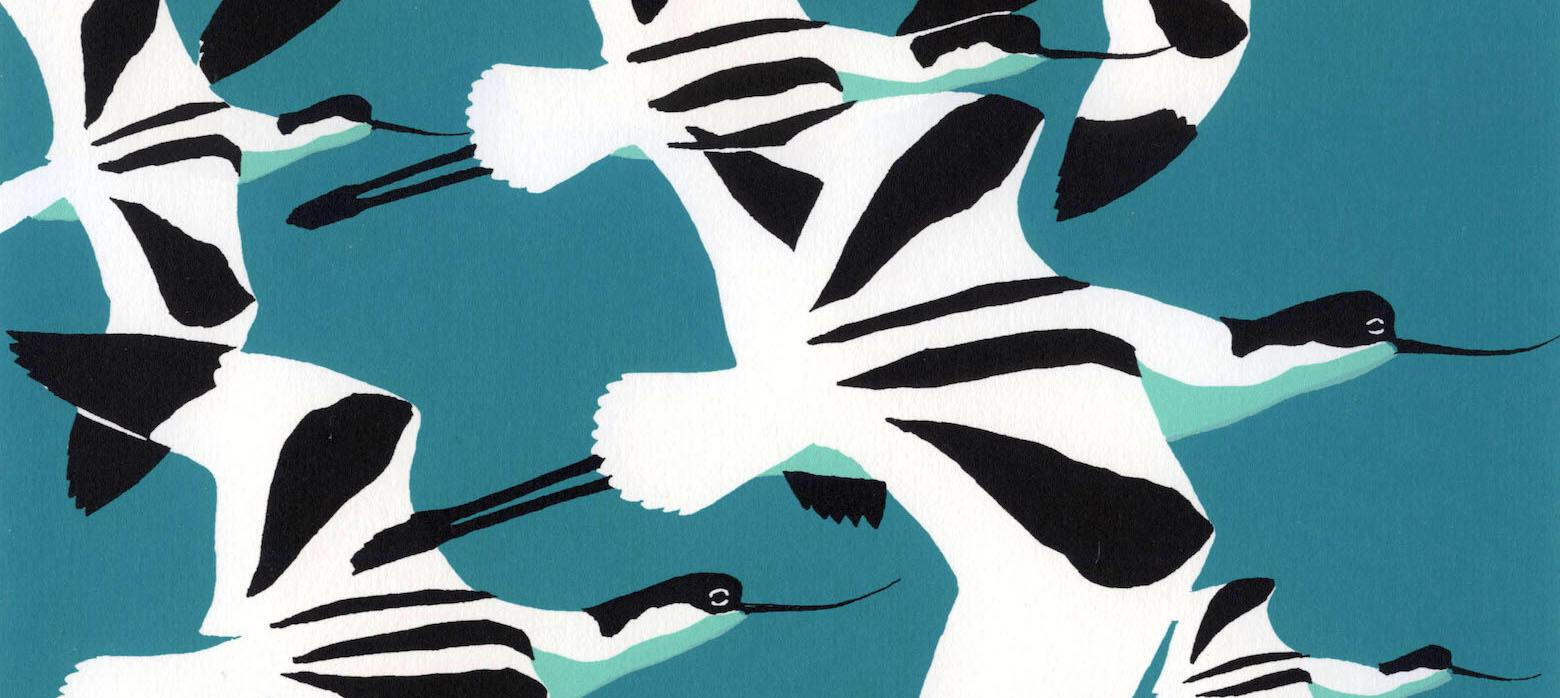

Charles Tunnicliffe (1901-1979), the son of a farmer, was a naturally gifted artist who eventually became a student at the Royal College of Art where he obtained the Painting School Diploma with distinction. He went on to join the RCA Engraving School where he made many etchings, mostly based on his experience of the Cheshire countryside where he had grown up. It was not until later, when asked to illustrate Henry Williamson’s book on the Peregrine Falcon, that he discovered in birds, and other natural history subjects, the direction in which he wanted to go. For instance, he delighted particularly in the pattern created by groups of birds. His work was characterised by his knowledge of the living bird, gained from his constant use of the sketchbook in the field. As a result, his work has an immediacy and freshness, lacking in much earlier work. Most of his major pictures are inspired by something he had seen when out in the countryside around his home.

A Natural Progression

Gradually, artists broke away from the stifling tradition of illustration to express ideas about wildlife, and to use the subject of wildlife to express ideas about design and composition, pattern and colour. They were no longer concerned to get every detail right in the photographic sense.

Wildlife art started to divide between the traditionalists who wished to represent their subjects with photographic precision and those who wanted to explore other approaches, already familiar to other branches of art.

The work of Richard Talbot Kelly (1896-1971) and Eric Ennion (1900-1981) owed little to what had gone before, in Europe at any rate. Like many artists at the start of the twentieth century, they were well aware of Oriental art, especially the printmakers of China and Japan, and its very different background to that of the European tradition. Talbot Kelly and Ennion had a considerable influence on aspiring young wildlife artists, particularly a group based at the Royal College of Art in the sixties and seventies. Working directly from life is all-important to these artists and much of their work is, actually, done in the field and then exhibited, sometimes even showing signs of exposure to the inclement weather of the moment.

The SWLA and Contemporary Wildlife Art

In the fifties, there were very few opportunities to see original pictures by wildlife artists, other than in their published works, books and cards. There was one ‘huntin, shootin and fishin’ gallery in Piccadilly, London that showed original paintings by the few leading wildlife artists. Otherwise, it was left to a group of 28 enthusiastic bird artists to launch the first ‘Exhibition by Contemporary Bird Painters’ which opened in November 1960. The success of this exhibition encouraged a small group of artists, including Robert Gillmor, Eric Ennion, Peter Scott, Keith Shackleton, Maurice Wilson and R.B. Talbot Kelly, to set about forming the Society of Wildlife Artists. The inaugural exhibition of the Society, with 35 founder members, was held in August 1964. Nearly 50 years later, the Society has around 80 members and sets the standard for wildlife art in Britain.

Today, much of the work might seem very strange to Gould or Thorburn. The emphasis is no longer on a scientifically accurate illustration of the species, however beautifully done, but on an interest in its character, how it belongs in its often tiny share of habitat, the impression it creates, the pattern of a group, some aspect of its behaviour, or simply the artist’s sheer enjoyment of the encounter. Sadly, a lot of other wildlife art is none of these things, but little more than a poorly drawn copy of a photograph of a species never seen in the wild by the artist.

The SWLA has a solid core of younger artists who are not stuck in an old tradition but who are forging a new and exciting approach to wildlife art. This approach is based on long and concentrated study in the field to get to the very essence of their subject and on finding new ways to interpret that understanding.

The emphasis is no longer on a scientifically accurate illustration of the species, however beautifully done, but on an interest in its character, how it belongs in its often tiny share of habitat, the impression it creates, the pattern of a group, some aspect of its behaviour, or simply the artist’s sheer enjoyment of the encounter.